Abstract

Capecitabine is a novel oral fluoropyrimidine carbamate that is preferentially converted to the cytotoxic moiety fluorouracil (5-fluorouracil; 5-FU) in target tumour tissue through a series of 3 metabolic steps. After oral administration of 1250 mg/m2, capecitabine is rapidly and extensively absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract [with a time to reach peak concentration (tmax) of 2 hours and peak plasma drug concentration (Cmax) of 3 to 4 mg/L] and has a relatively short elimination half-life (t1/2) [0.55 to 0.89h]. Recovery of drug-related material in urine and faeces is nearly 100%.

Plasma concentrations of the cytotoxic moiety fluorouracil are very low [with a Cmax of 0.22 to 0.31 mg/L and area under the concentration-time curve (AUC) of 0.461 to 0.698 mg · h/L]. The apparent t1/2 of fluorouracil after capecitabine administration is similar to that of the parent compound.

Comparison of fluorouracil concentrations in primary colorectal tumour and adjacent healthy tissues after capecitabine administration demonstrates that capecitabine is preferentially activated to fluorouracil in colorectal tumour, with the average concentration of fluorouracil being 3.2-fold higher than in adjacent healthy tissue (p = 0.002). This tissue concentration differential does not hold for liver metastasis, although concentrations of fluorouracil in liver metastases are sufficient for antitumour activity to occur. The tumour-preferential activation of capecitabine to fluorouracil is explained by tissue differences in the activity of cytidine deaminase and thymidine Phosphorylase, key enzymes in the conversion process.

As with other cytotoxic drugs, the interpatient variability of the pharmacokinetic parameters of capecitabine and its metabolites, 5′-deoxy-5-fluorocytidine and fluorouracil, is high (27 to 89%) and is likely to be primarily due to variability in the activity of the enzymes involved in capecitabine metabolism. Capecitabine and the fluorouracil precursors 5′-deoxy-5-fluorocytidine and 5′-deoxy-5-fluorouridine do not accumulate significantly in plasma after repeated administration. Plasma concentrations of fluorouracil increase by 10 to 60% during long term administration, but this time-dependency is assumed to be not clinically relevant.

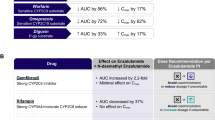

A potential drug interaction of capecitabine with warfarin has been observed. There is no evidence of pharmacokinetic interactions between capecitabine and leucovorin, docetaxel or paclitaxel.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Thomas CM, Zalcberg JR. 5-Fluorouracil: a pharmacological paradigm in the use of cytotoxics. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 1998; 25: 887–95

Advanced Colorectal Cancer Meta-Analysis Project. Modulation of fluorouracil by leucovorin in patients with advanced colorectal cancer: evidence in terms of response rate. J Clin Oncol 1992; 10: 896–903

International Multicentre Pooled Analysis of Colon Cancer Trials (IMPACT) Investigators. Efficacy of adjuvant fluorouracil and folinic acid in colon cancer. Lancet 1995; 345: 939–44

Meta-Analysis Group in Cancer. Efficacy of intravenous continuous infusion of fluorouracil compared with bolus administration in advanced colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 1998; 16: 301–8

Caudry M, Bonnel C, Floquet A, et al. A randomized study of bolus fluorouracil plus folinic acid versus 21-day fluorouracil infusion alone or in association with cyclophosphamide and mitomycin C in advanced colorectal carcinoma. Am J Clin Oncol 1995; 18: 118–25

Hryniuk WM, Figueredo A, Goodyear M. Applications of dose intensity to problems in chemotherapy of breast and colorectal cancer. Semin Oncol 1987; 14: 3–11

Diasio RB. The role of dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPD) modulation in 5-FU pharmacology. Oncology (Hunting!) 1998; 12(10 Suppl.): 23–7

Meropol NJ. Oral fluoropyrimidines in the treatment of colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer 1998; 34: 1509–13

Pazdur R, Hoff PM, Medgyesy D, et al. The oral fluorouracil prodrugs. Oncology (Huntingt) 1998; 12: 48–51

Van Cutsem E, Findlay M, Osterwalder B, et al. Capecitabine (Xeloda®), an oral fluoropyrimidine carbamate with substantial activity in advanced colorectal cancer: results of a randomized phase II study. J Clin Oncol 2000; 18: 1337–45

Blum JL, Jones SE, Buzdar AU, et al. Multicenter phase II study of capecitabine in paclitaxel-refractory metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 1999; 17: 485–93

Twelves C, Harper P, Van Cutsem E, et al. A phase III trial (SO 14796) of Xeloda® (capecitabine) in previously untreated advanced/metastatic colorectal cancer [abstract]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1999; 35: 263

Cox JV, Pazdur R, Thibault A, et al. A phase III trial (SO 14695) of Xeloda® (capecitabine) in previously untreated advanced/metastatic colorectal cancer [abstract]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1999; 35: 265

Investigator’s brochure of capecitabine. Nutley (NJ): Hoffmann-La Roche, 2000 Mar. (Data on file)

Schüller J, Cassidy J, Dumont E, et al. Preferential activation of capecitabine in tumor following oral administration in colorectal cancer patients. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2000; 45: 291–7

Cassidy J, Twelves C, Cameron D, et al. Bioequivalence of two tablet formulations of capecitabine and exploration of age, gender, body surface area, and Creatinine clearance as factors influencing systemic exposure in cancer patients. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 1999; 44: 453–60

Reigner B, Verweij J, Dirix L, et al. Effect of food on the pharmacokinetics of capecitabine and its metabolites following oral administration in cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res 1998; 4: 941–8

Reigner B, Clive S, Cassidy J, et al. Influence of Maalox on the pharmacokinetics of capecitabine in cancer patients. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 1999; 43: 309–15

Twelves C, Glynne-Jones R, Cassidy J, et al. Effect of hepatic dysfunction due to liver metastases on the pharmacokinetics of capecitabine and its metabolites. Clin Cancer Res 1999; 5: 1696–702

Mackean M, Planting A, Twelves C, et al. A phase 1 study of intermittent twice daily oral therapy with capecitabine in patients with advanced and/or metastatic solid cancer. J Clin Oncol 1998; 16: 2977–85

Miwa M, Ura M, Nishida M, et al. Design of a novel oral fluoropyrimidine carbamate, capecitabine, which generates 5-fluorouracil selectively in tumors by enzymes concentrated in human liver and cancer tissue. Eur J Cancer 1998; 34: 1274–81

Ho DH, Townsend L, Luna MA, et al. Distribution and inhibition of dihydrouracil dehydrogenase activities in human tissues using 5-fluorouracil as a substrate. Anticancer Res 1986; 6: 781–4

Lu Z, Zhang R, Diasio RB. Dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase activity in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells and liver: population characteristics, newly identified deficient patients, and clinical implications in 5-fluorouracil chemotherapy. Cancer Res 1993; 53: 5433–8

Takimoto CH, Lu ZH, Zhang R, et al. Severe neurotoxicity following 5-fluorouracil-based chemotherapy in a patient with dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase deficiency. Clin Cancer Res 1996; 2: 477–81

Houyau P, Gay C, Chatelut E, et al. Severe fluorouracil toxicity in a patient with dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase deficiency. J Natl Cancer Inst 1993; 85: 1602–3

Etienne MC, Lagrange JL, Dassonville O, et al. Population study of dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase in cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 1994; 12: 2248–53

Diasio RB, Harris BE. Clinical pharmacology of 5-fluorouracil. Clin Pharmacokinet 1989; 16: 215–37

Peters GJ, Lankelma J, Kok RM, et al. Prolonged retention of high concentrations of 5-fluorouracil in human and murine tumors compared with plasma. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 1993; 31: 269–76

Nio Y, Kimura H, Tsubono M, et al. Antitumor activity of 5t-deoxy-5-fluorouridine in human digestive organ cancer xenografts and pyrimidine nucleoside Phosphorylase activity in normal and neoplastic tisues from human digestive organs. Anticancer Res 1992; 12: 1141–6

Peters GJ, van Groeningen CJ, Laurensse EJ, et al. A comparison of 5-fluorouracil metabolism in human colorectal cancer and colon mucosa. Cancer 1991; 68: 1903–9

Guimbaud R, Guichard S, Dusseau C, et al. Dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase activity in normal, inflammatory and tumor tissues of colon and liver in humans. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2000; 45: 477–82

Ishikawa T, Sekiguchi F, Fukase Y, et al. Positive correlation between the efficacy of capecitabine and doxifluridine and the ratio of thymidine Phosphorylase to dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase activities in tumors in human cancer xenografts. Cancer Res 1998; 58: 685–90

Milano G, McLeod HL. Can dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase impact 5-fluorouracil-based treatment? Eur J Cancer 2000; 36: 37–42

Kovach JS, Beart RW. Cellular pharmacology of fluorinated pyrimidines in vivo in man. Invest New Drugs 1989; 7: 13–25

Christophidis N, Vajda FJE, Lucas I, et al. Fluorouracil therapy in patients with carcinoma of large bowel: a pharmacokinetic comparison of various rates and routes of administration. Clin Pharmacokinet 1978; 3: 330–6

Heggie GD, Sommadossi JP, Cross DS, et al. Clinical pharmacokinetics of 5-fluorouracil and its metabolites in plasma, urine and bile. Cancer Res 1987; 47: 2203–6

In vitro plasma protein binding of Ro 09-1978, 5′DFCR and 5′DFUR in human and animal. Kamakura: Hoffmann-La Roche, 1997 Aug. (Data on file)

Judson IR, Beale PJ, Trigo JM, et al. A human capecitabine excretion balance and pharmacokinetic study after administration of a single oral dose of 14C-labelled drug. Invest New Drugs 1999; 17: 49–56

Budman DR, Meropol NJ, Reigner B, et al. Preliminary studies of a novel oral fluoropyrimidine carbamate: capecitabine. J Clin Oncol 1998; 16: 1795–802

Noncompartmental analysis based on the statistical moment therapy. In: Gibaldi M, Perrier D, editors. Pharmacokinetics. 2nd ed. New York: Marcel Dekker, 1982: 409–16

Cassidy J, Dirix L, Bissett D, et al. A phase I study of capecitabine in combination with oral leucovorin in patients with intractable solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res 1998; 4: 2755–61

Villalona-Calero MA, Weiss GR, Durris HA, et al. Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of the oral fluoropyrimidine capecitabine in combination with paclitaxel in patients with advanced solid malignancies. J Clin Oncol 1999; 17: 1915–25

Lu Z, Zhang R, Carpenter JT, et al. Decreased dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase activity in a population of patients with breast cancer: implication for 5-fluorouracil-based chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res 1998; 4: 325–9

Gieschke R, Steimer JL, Reigner B. Relationships between metrics of exposure to Xeloda® and occurrence of adverse effects [abstract No 7-861]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1998; 17: 223

Moore MJ, Theissen JJ. Cytotoxics and irreversible effects. In: van Boxtel CJ, Holford NHG, Danhof M, editors. The in vivo study of drug action. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 1992: 379

Janknegt D. Drug interactions with quinolones. J Antimicrob Chemother 1990; 26 Suppl. D: 7–29

Harcourt RS, Hamburger M. The effect of magnesium sulfate in lowering tetracycline blood levels. J Lab Clin Med 1957; 50: 464–8

Arnold LA, Spurbeck GH, Shelver WH, et al. Effect of an antacid on gastrointestinal absorption of theophylline. Am J Hosp Pharm 1979; 36: 1059–62

Chase JL, Ignoffo RJ, Stagg RJ. Gastrointestinal cancers. In: DiPiro JT, Talbert RL, Hayes PE, et al., editors. Pharmacotherapy, a pathophysiologic approach. New York: Elsevier, 1988: 1384

Poon MA, O’Connell MJ, Wieand HS, et al. Biochemical modulation of fluorouracil with leucovorin: confirmatory evidence of improved therapeutic efficacy in advanced colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 1991; 9: 1967–72

Buroker TR, O’Connell MJ, Wieand HS, et al. Randomized comparison of two schedules of fluorouracil and leucovorin in the treatment of advanced colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 1994; 12: 14–20

Rowinsky EK, Donehower RC. The clinical pharmacology and use of antimicrotubule agents in cancer chemotherapeutics. Pharmacol Ther 1991; 52: 35–84

Ringel I, Horwitz SB. Studies with RP 56976 (Taxotere): a semisynthetic analog of Taxol. J Natl Cancer Inst 1991; 83: 288–91

Sawada N, Ishikawa T, Fukase Y, et al. Induction of thymidine Phosphorylase activity and enhancement of capecitabine efficacy by Taxol/Taxotere in human cancer xenografts. Clin Cancer Res 1998; 4: 1013–9

Bogdan C, Ding A. Taxol, a microtubule stabilizing antineoplastic agent, induces expression of tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-1 in macrophages. J Leukoc Biol 1992; 52: 119–21

Pronk L, Vasey P, Sparreboom A, et al. A matrix-designed phase I dose-finding and pharmacokinetic study of the combination of capecitabine (Xeloda®) and docetaxel (Taxotere®) in patients with advanced solid tumors. Br J Cancer 2000; 83: 22–9

Kolesar JM, Johnson CL, Freeberg BL, et al. Warfarin-5-FU interaction: a consecutive case series. Pharmacotherapy 1999; 19(12): 1445–9

IN vitro drug interaction studies with capecitabine (Ro 09-1978) and furtulon (Ro 21-9738) using human liver microsomes. Nutley (NJ): Hoffmann La Roche, 1997 Aug. (Data on file)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Reigner, B., Blesch, K. & Weidekamm, E. Clinical Pharmacokinetics of Capecitabine. Clin Pharmacokinet 40, 85–104 (2001). https://doi.org/10.2165/00003088-200140020-00002

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00003088-200140020-00002