Abstract

Background:

Ethnic disparities in breast cancer diagnoses and disease-specific survival (DSS) rates in the United States are well known. However, few studies have assessed differences specifically between Asians American(s) and other ethnic groups, particularly among Asian American(s) subgroups, in women aged 18–39 years.

Methods:

The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database was used to identify women aged 18–39 years diagnosed with breast cancer from 1973 to 2009. Incidence rates, clinicopathologic features, and survival among broad ethnic groups and among Asian subgroups.

Results:

A total of 55 153 breast cancer women aged 18–39 years were identified: 63.6% non-Hispanic white (NHW), 14.9% black, 12.8% Hispanic-white (HW), and 8.7% Asian. The overall incidence rates were stable from 1992 to 2009. Asian patients had the least advanced disease at presentation and the lowest risk of death compared with the other groups. All the Asian subgroups except the Hawaiian/Pacific Islander subgroup had better DSS than NHW, black, and HW patients. Advanced tumour stage was associated with poorer DSS in all the ethnic groups. High tumour grade was associated with poorer DSS in the NHW, black, HW, and Chinese groups. Younger age at diagnosis was associated with poorer DSS in the NHW and black groups.

Conclusion:

The presenting clinical and pathologic features of breast cancer differ by ethnicity in the United States, and these differences impact survival in women younger than 40 years.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women and the leading cause of cancer death among women in all ethnic groups worldwide (NHS, 2013). However, breast cancer is uncommon in young women: only ∼7% of all breast cancers are diagnosed in women younger than 40 years, and fewer than 4% are diagnosed in women younger than 35 years (Chung et al, 1996; Brinton et al, 2008). Nonetheless, a recent study showed a small but significant increase in the incidence of breast cancer with distant disease in the United States in relatively young women aged 25–39 years from 1976 to 2009 (Johnson et al, 2013), causing some concern and prompting further studies to confirm the findings and to determine the potential reasons.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that breast tumours in younger women have a more aggressive biology, which correlates with poorer outcomes when compared with older women (Nixon et al, 1994; Chung et al, 1996; Dubsky et al, 2002; Han et al, 2004; Aebi and Castiglione, 2006). However, data regarding disparities among these young women are limited. The few studies that have been published have focused on comparisons among black, Hispanic, and white women (Newman et al, 2002; Shavers et al, 2003). In a study of breast cancer patients of all ages, our group previously found that patients in all Asian subgroups were younger at diagnosis than NHW patients except Japanese patients, and patients in most Asian subgroups had similar survival rates compared with NHW women except Japanese patients had a better survival rate and Hawaiian/Pacific Islander patients had a worse survival rate (Yi et al, 2012). The current study was performed to identify disparities specifically in young women. Using age 39 years as a cutoff, we sought to identify differences in disease presentation, clinicopathologic features, and survival among the broad ethnic groups and among the Asian subgroups.

Patients and methods

Patient selection and data collection

The Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database of the National Cancer Institute was used to identify patients with primary tumour sites coded as C50.0–C50.9 (breast) between 1973 and 2009. Data were obtained from all 18 US cancer registries participating in the SEER program using SEER*Stat software version 8.0.2 (http://seer.cancer.gov/seerstat). Male patients and patients whose race was coded as ‘American Indian/Alaska Native’, ‘Other unspecified (1991+)’, or ‘Unknown’ were excluded. Ethnicity was categorised into four broad groups: non-Hispanic-white (NHW), black, Hispanic white (HW), and Asian. Eight subgroups of Asian patients were identified: Filipino, Chinese, Japanese, Asian Indian/Pakistani, Korean, Vietnamese, Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and others.

Statistical analysis

Age-adjusted breast cancer SEER incidence rates in women aged 18–39 years and older than 39 years were calculated separately by using SEER*Stat software version 8.0.2 and data from incidence – SEER 13 (1992–2009). A χ2 test was used to assess differences in categorical variables (disease stage, surgery type, tumour grade, hormone receptor status and radiation treatment status) and a Kruskal–Wallis equality-of-populations rank test was used to assess differences in continue variables (age at diagnosis) among the broad ethnic groups and among the eight Asian subgroups.

Overall survival (OS) was calculated from the date of diagnosis to the date of death, date last known to be alive, or 30 November 2009, whichever occurred first. Disease-specific survival (DSS) was calculated from the date of diagnosis to the date of breast cancer-related death, date last known to be alive, or 30 November 2009. Overall survival and DSS curves were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method. Patients who were lost to follow-up or who survived beyond 30 November 2009, were censored.

Multivariate Cox proportional hazards models were used to determine the influence of patient, tumour, and treatment factors of known or potential prognostic value on DSS in each broad ethnic group and in each Asian subgroup with a sample of >500 patients. Stata SE version 12.0 statistical software (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) was used for statistical analyses. All tests were two-tailed, and statistical significance was set at P<0.05.

Results

Patient and tumour characteristics

The SEER database revealed 971 565 patients diagnosed with breast cancer from 1973 to 2009, including 55 908 (5.8%) aged 18–39 years. Hispanic white had the highest percentage of patients whose age at diagnosis was between 18 and 39 years old (10.8%) while NHW had the lowest percentage (4.7%, black patients (9.5%), and Asian patients (8.6%)). Of these, 55 153 patients belonged to 1 of the 4 broad ethnic groups being evaluated in this study: 35 101 (63.6%) NHW, 8215 (14.9%) black, 7067 (12.8%) HW, and 4770 (8.7%) Asian.

The clinicopathologic characteristics of patients in the broad ethnic groups are shown in Table 1. Our analyses revealed differences among the groups with respect to disease stage, surgery type, tumour grade, oestrogen receptor (ER) status, progesterone receptor (PR) status, and radiation treatment status. The incidence of localised tumours was higher in Asian patients (52.9%) than in NHW (51.6%, P=0.1), black (44.3%, P<0.0001), and HW (44.3%, P<0.0001) patients. The incidence of distant disease was higher in black patients (8.3%) than in patients in any of the other three groups (NHW 4.6%, HW 6.8%, and Asian 4.8%). At least 55% of patients in each broad ethnic group had undergone total mastectomy. The incidence of grade III and IV tumours was lowest in the Asian patients (56.3%) and highest in the black patients (70.5%). At least 75% of patients in each broad ethnic group had invasive ductal carcinoma. The incidence of ER-positive tumours was highest in the Asian patients (67.8%) and lowest in the black patients (49.9%). In all, 70% Asian patients received radiation therapy after segmental mastectomy while only 62.2% black patients received radiation theory after segmental mastectomy (P<0.0001).

The Asian patients were categorised into eight subgroups as follows: Filipino (21.8%), Chinese (20.9%), Japanese (12.6%), Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (11.3%), Korean (7.1%), Asian Indian/Pakistani (8.6%), Vietnamese (6.4%), and other (11.2%). Table 2 lists the clinicopathologic characteristics of patients in the eight subgroups. Disease stage at presentation, tumour histology and grade, and ER and PR status were different among the subgroup. Japanese patients generally had more favourable clinicopathologic features: they had the highest incidence of localised disease (59.3%) and grade I tumours (12.3%). Asian Indian/Pakistani women generally had less favourable clinicopathologic features: they had the highest incidence of regional/distant disease (56.3%) and grade III/IV tumours (64.2%) and the lowest incidence of ER-positive tumours (61.0%). As in the broad ethnic group comparisons, the majority of patients in all the subgroups had undergone surgery. The smallest proportion of patients who did not undergo surgery was in the Japanese subgroup (2.0%), whereas the largest proportion of patients who did not undergo surgery was in the Asian Indian/Pakistani subgroup (5.9%). There were no difference in received radiation therapy after segmental mastectomy among Asian subgroups (P=0.8). In all, 45% Asian Indian/Pakistani received radiation therapy after total mastectomy while only 26.5% Vietnamese received radiation therapy (P<0.0001).

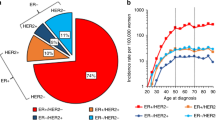

Breast cancer incidence rates

Figure 1 shows age-adjusted breast cancer incidence rates in women aged 18–39 years (A) and older than 39 years (B) from the SEER 13 registries (1992–2009). Although the incidence rates for patients older than 39 years decreased during this time period, the incidence rates for women aged 18–39 years were stable. In this younger age group, black patients had the highest incidence rates, and two dramatic increases were noted in 2000 and 2004. In young NHW women, there was a slight increase from 1992 to 2009, whereas the incidence rates in HW women were slightly decreased. Incidence rates in Asian women were decreased from 1992 to 1997, increased from 1997 to 2001, and aside from an increase in 2008 in the 18–39 age group, then decreased again. Incidence rates in the Asian subgroups were not available.

Survival

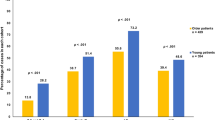

The median follow-up for the study cohort was 6 years. The 5- and 10-year DSS and OS rates are shown in Table 3. Korean and Japanese patients had the best 5-year DSS rates (89.3% and 86.0%, respectively), and black and Hawaiian/Pacific Islander patients had the poorest 5-year DSS rates (71.8% and 76.1%, respectively). All Asian subgroups except Hawaiian patients (75.9%) had a better 5-year OS rate than did NHW, black, and HW patients (80.0%, 69.4%, and 77.0%, respectively).

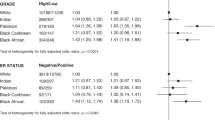

Table 4 shows the association between clinicopathologic factors and DSS in the four broad ethnicity groups. Advanced tumour stage, high tumour grade, and negative ER status were highly associated with poorer DSS in each ethnic group. Age younger than 35 years was associated with poorer DSS in NHW and black patients but not in HW or Asian patients. Table 5 shows the association between clinicopathologic factors and DSS in four Asian ethnicity subgroups that had a sample of >500 patients (Filipino, Japanese, Chinese, and Hawaiian/Pacific Islander). Advanced tumour stage was highly associated with poorer DSS in all four subgroups. Higher tumour grade was associated with poorer DSS in only in the Chinese subgroup. The ER-negative status was associated with DSS in the Hawaiian subgroup only. Age at diagnosis was not associated with DSS in these four Asian subgroups.

Discussion

The current study represents one of the most comprehensive population-based analyses of breast cancer patients aged 18–39 years evaluated by ethnicity. Our study included >55 000 (5.8%) breast cancer women aged 18–39 years, which is comparable to the 7% of breast cancer patients aged 18–39 years reported in other studies (Chung et al, 1996; Brinton et al, 2008). Consistent with other studies (Gray et al, 1980; Pathak et al, 2000; Joslyn et al, 2005; Brinton et al, 2008) our study showed that black women had higher incidence rates of breast cancer than NHW women before age 40, whereas NHW women had higher incidence rates than black women after age 39 (crossover pattern). The HW and Asian women had lower breast cancer incidence rates than NHW women in both age groups and did not exhibit the crossover pattern observed among black women. Interestingly, for women aged 18–39 years, the incidence rates were increased only in NHW women from 1992 to 2009. This observation must be put into context, however, as in NHW patients, only 4.7% of breast cancers were diagnosed in patients aged 18–39 years, compared with 10.8% in the HW patients, 9.5% in the black patients, and 8.6% in the Asian patients, numbers that are consistent with previously published reports (Chung et al, 1996; Brinton et al, 2008; Telli et al, 2011; Yi et al, 2012). It is possible the overall age distribution of Asian women is younger compared with the other ethnic groups in the United States, resulting in a disproportionate breakdown by age. This could be due to immigration patterns, as the Asian population reflects the rapid increases in younger age in the latter half of the twentieth century.

Interestingly, the Asian patients in our study presented with less advanced stages of disease and had a lower risk of death compared with patients in the other ethnic groups. This finding conflicts with the findings of previous studies that included patients of all ages, which showed that Asian patients were more likely to have advanced disease than NHW patients but less likely to have advanced disease than black and HW patients (Li et al, 2003; Martinez et al, 2007; Berz et al, 2009; Ooi et al, 2011; Yi et al, 2012). Among the Asian subgroups, Asian Indian/Pakistani patients had the highest proportion of patients with advanced disease, high tumour grades, and ER- and PR-negative tumours, but their mortality risk was similar to that in the other subgroups, which is consistent with previous studies evaluating Asian women of all ages (Moran et al, 2011; Yi et al, 2012). Hawaiian/Pacific Islander patients had the poorest DSS of all the Asian subgroups even though they were comparable to the other subgroups in terms of disease stage and tumour grade, which is consistent with the findings we previously published from a study evaluating patients in all age groups (Yi et al, 2012). These data suggest that this subgroup may experience issues related to access to care (i.e., screening and follow-up) rather than differences in tumour biology (Ooi et al, 2011).

Our study also showed that age as a risk factor for DSS varied between ethnic groups. Although being younger than 35 at diagnosis was associated with poorer DSS in NHW and black patients, it was not associated with DSS in HW patients or Asian patients. Our study also showed that there was no survival difference in Asian subgroups when compared patients younger than 35 with 35–39, which is consistent with the studies conducted in Japan (Yoshida et al, 2011) and Korean (Kim et al, 2007). This may suggest that, in HW and Asian groups, tumour biology and age are independent prognostic factors for survival. An interesting observation in our study is the differences in biologic factors between Asians and other ethnic groups, specifically in tumour grade, ER/PR status, and % presenting with localised disease. Previous studies have shown that certain breast cancer subtypes to include triple-negative breast cancer (Bauer et al, 2007; Millikan et al, 2008) occur more often in young patients. Although population-based studies have identified a higher proportion of triple negative breast cancers in premenopausal Black women (Carey et al, 2006; Bauer et al, 2007; Morris et al, 2007), the relationship between race and tumour biology has not been completely elucidated. Ongoing work by our group is further investigating the relationship among age, race, and tumour biology in Asian patients.

Because this study was a retrospective investigation of a population-based database, data regarding socioeconomic status, family history of breast cancer, lifestyle factors, Her2 status, and the administration of neoadjuvant or adjuvant systemic therapies were limited. This prevented us from evaluating these factors as potential confounders or effect modifiers of the relationships observed. In addition, SEER age-adjusted incidence rates were limited to the four broad ethnic groups only because no data were available for Asian subgroups. Incidence rates were also limited to the time period from 1992 to 2009, when data were available. The long duration of our study period (1973–2009) may affect the results due to missing data and change of management. Instead of using TNM stage, we only used localised, regional, distant as disease stage. We cannot provide information about non-invasive disease or DCIS in our study.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that presenting clinical and pathologic features of breast cancer differ by ethnicity in the United States and that these differences impact survival in women younger than age 40 years.

Change history

03 September 2013

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Aebi S, Castiglione M (2006) The enigma of young age. Ann Oncol 17 (10): 1475–1477.

Bauer KR, Brown M, Cress RD, Parise CA, Caggiano V (2007) Descriptive analysis of estrogen receptor (ER)-negative, progesterone receptor (PR)-negative, and HER2-negative invasive breast cancer, the so-called triple-negative phenotype: a population-based study from the California cancer Registry. Cancer 109 (9): 1721–1728.

Berz JP, Johnston K, Backus B, Doros G, Rose AJ, Pierre S, Battaglia TA (2009) The influence of black race on treatment and mortality for early-stage breast cancer. Med Care 47 (9): 986–992.

Brinton LA, Sherman ME, Carreon JD, Anderson WF (2008) Recent trends in breast cancer among younger women in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst 100 (22): 1643–1648.

Carey LA, Perou CM, Livasy CA, Dressler LG, Cowan D, Conway K, Karaca G, Troester MA, Tse CK, Edmiston S, Deming SL, Geradts J, Cheang MC, Nielsen TO, Moorman PG, Earp HS, Millikan RC (2006) Race, breast cancer subtypes, and survival in the Carolina Breast Cancer Study. JAMA 295 (21): 2492–2502.

Chung M, Chang HR, Bland KI, Wanebo HJ (1996) Younger women with breast carcinoma have a poorer prognosis than older women. Cancer 77 (1): 97–103.

Dubsky PC, Gnant MF, Taucher S, Roka S, Kandioler D, Pichler-Gebhard B, Agstner I, Seifert M, Sevelda P, Jakesz R (2002) Young age as an independent adverse prognostic factor in premenopausal patients with breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer 3 (1): 65–72.

Gray GE, Henderson BE, Pike MC (1980) Changing ratio of breast cancer incidence rates with age of black females compared with white females in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst 64 (3): 461–463.

Han W, Kim SW, Park IA, Kang D, Youn YK, Oh SK, Choe KJ, Noh DY (2004) Young age: an independent risk factor for disease-free survival in women with operable breast cancer. BMC Cancer 4: 82.

Johnson RH, Chien FL, Bleyer A (2013) Incidence of breast cancer with distant involvement among women in the United States, 1976 to 2009. JAMA 309 (8): 800–805.

Joslyn SA, Foote ML, Nasseri K, Coughlin SS, Howe HL (2005) Racial and ethnic disparities in breast cancer rates by age: NAACCR Breast Cancer Project. Breast Cancer Res Treat 92 (2): 97–105.

Kim JK, Kwak BS, Lee JS, Hong SJ, Kim HJ, Son BH, Ahn SH (2007) Do very young Korean breast cancer patients have worse outcomes? Ann Surg Oncol 14 (12): 3385–3391.

Li CI, Malone KE, Daling JR (2003) Differences in breast cancer stage, treatment, and survival by race and ethnicity. Arch Intern Med 163 (1): 49–56.

Martinez ME, Nielson CM, Nagle R, Lopez AM, Kim C, Thompson P (2007) Breast cancer among Hispanic and non-Hispanic White women in Arizona. J Health Care Poor Underserved 18 (4 Suppl): 130–145.

Millikan RC, Newman B, Tse CK, Moorman PG, Conway K, Dressler LG, Smith LV, Labbok MH, Geradts J, Bensen JT, Jackson S, Nyante S, Livasy C, Carey L, Earp HS, Perou CM (2008) Epidemiology of basal-like breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 109 (1): 123–139.

Moran MS, Gonsalves L, Goss DM, Ma S (2011) Breast cancers in U.S. residing Indian-Pakistani versus non-Hispanic White women: comparative analysis of clinical-pathologic features, treatment, and survival. Breast Cancer Res Treat 128 (2): 543–551.

Morris GJ, Naidu S, Topham AK, Guiles F, Xu Y, McCue P, Schwartz GF, Park PK, Rosenberg AL, Brill K, Mitchell EP (2007) Differences in breast carcinoma characteristics in newly diagnosed African-American and Caucasian patients: a single-institution compilation compared with the National Cancer Institute's Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database. Cancer 110 (4): 876–884.

Newman LA, Bunner S, Carolin K, Bouwman D, Kosir MA, White M, Schwartz A (2002) Ethnicity related differences in the survival of young breast carcinoma patients. Cancer 95 (1): 21–27.

NHS (2013) NHS Breast Screening Programmes. Breast Cancer, Paragraph 1.2 http://www.cancerscreening.nhs.uk/breastscreen/breastcancer.html#incidence.

Nixon AJ, Neuberg D, Hayes DF, Gelman R, Connolly JL, Schnitt S, Abner A, Recht A, Vicini F, Harris JR (1994) Relationship of patient age to pathologic features of the tumor and prognosis for patients with stage I or II breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 12 (5): 888–894.

Ooi SL, Martinez ME, Li CI (2011) Disparities in breast cancer characteristics and outcomes by race/ethnicity. Breast Cancer Res Treat 127 (3): 729–738.

Pathak DR, Osuch JR, He J (2000) Breast carcinoma etiology: current knowledge and new insights into the effects of reproductive and hormonal risk factors in black and white populations. Cancer 88 (5 Suppl): 1230–1238.

Shavers VL, Harlan LC, Stevens JL (2003) Racial/ethnic variation in clinical presentation, treatment, and survival among breast cancer patients under age 35. Cancer 97 (1): 134–147.

Telli ML, Chang ET, Kurian AW, Keegan TH, McClure LA, Lichtensztajn D, Ford JM, Gomez SL (2011) Asian ethnicity and breast cancer subtypes: a study from the California Cancer Registry. Breast Cancer Res Treat 127 (2): 471–478.

Yi M, Liu P, Li X, Mittendorf EA, He J, Ren Y, Nayeemuddin K, Hunt KK (2012) Comparative analysis of clinicopathologic features, treatment, and survival of Asian women with a breast cancer diagnosis residing in the United States. Cancer 118 (17): 4117–4125.

Yoshida M, Shimizu C, Fukutomi T, Tsuda H, Kinoshita T, Akashi-Tanaka S, Ando M, Hojo T, Fujiwara Y (2011) Prognostic factors in young Japanese women with breast cancer: prognostic value of age at diagnosis. Jpn J Clin Oncol 41 (2): 180–189.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, P., Li, X., Mittendorf, E. et al. Comparison of clinicopathologic features and survival in young American women aged 18–39 years in different ethnic groups with breast cancer. Br J Cancer 109, 1302–1309 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.387

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.387

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Breast cancer survival after mammography dissemination in Brazil: a population-based analysis of 2,715 cases

BMC Women's Health (2023)

-

The murine metastatic microenvironment of experimental brain metastases of breast cancer differs by host age in vivo: a proteomic study

Clinical & Experimental Metastasis (2023)

-

Race disparities in mortality by breast cancer from 2000 to 2017 in São Paulo, Brazil: a population-based retrospective study

BMC Cancer (2021)

-

High mobility group A1 (HMGA1) protein and gene expression correlate with ER-negativity and poor outcomes in breast cancer

Breast Cancer Research and Treatment (2020)

-

Analysis of breast cancer in young women in the Department of Defense (DOD) database

Breast Cancer Research and Treatment (2018)